How the Highland Park shooter avoided Illinois’ red flag law

(NewsNation) — In the wake of the Highland Park July Fourth shooting, questions have surfaced about how the gunman was allowed to buy firearms despite prior police contact and whether he slipped through the cracks of Illinois’ red flag law.

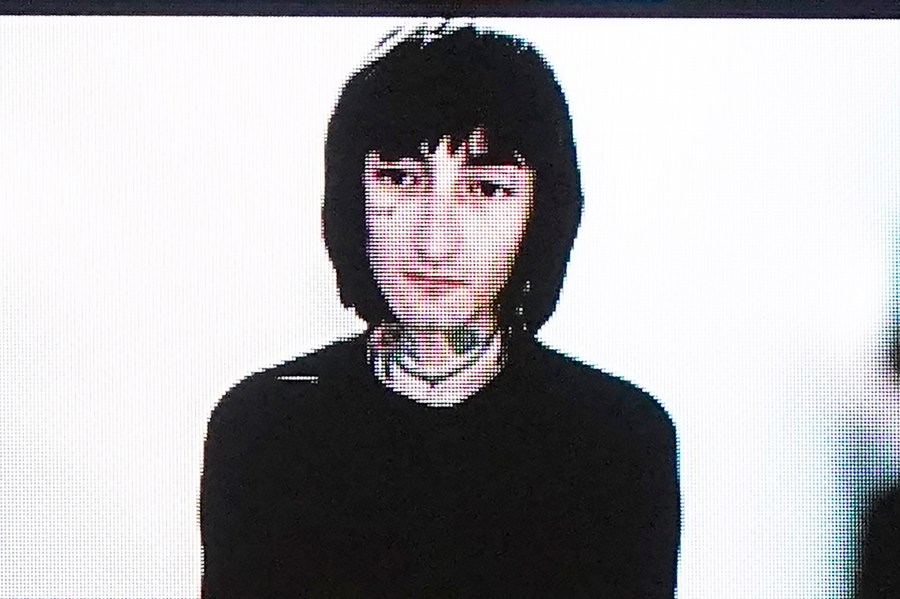

Robert Crimo III is accused of killing seven and injuring dozens at the Chicago suburb’s Fourth of July parade with a rifle he purchased legally.

Illinois’ red flag law could have prevented the alleged shooter from purchasing firearms — if the law was used as intended, according to Robert Spitzer, an author and political science professor at State University of New York College at Cortland.

“The Illinois red flag law could have played a role, perhaps a critical role, had either or both of the parents filed a report under the state red flag law, called the Illinois Firearms Restraining Order Act,” Spitzer said.

In Highland Park, the alleged gunman was known to authorities after two separate incidents in 2019.

Police first responded in April to a suicide attempt. That matter was handled by mental health professionals, according to Lake County Major Crime Task Force spokesman Christopher Covelli.

If you or someone you know is thinking of harming themself, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline provides free support at 1-800-273-8255. Starting on July 16, 2022, U.S. residents can also be connected to the Lifeline by dialing 988. For more about risk factors and warning signs, visit the organization’s official website.

Five months later, a family member called police saying he threatened to “kill everyone” in the home. State police said officers found knives during the call but they turned them over to the father, who was the owner.

Illinois State Police said they received a “clear and present danger” report after the alleged knife incident in 2019, but after Crimo’s father claimed the knives were his, he declined to move forward with a complaint. State police said there was no probable cause to make an arrest.

“That report disappears if there is no further action taken either by the police or by the suspect or by a family member, filing a report,” Spitzer said. “And that apparently is what happened in this case.”

Just months after the alleged knife incident, Crimo’s father sponsored his son’s gun license in December 2019, state police said. Crimo was 19 years old at the time. He later passed four different background checks between June 2020 and September 2021, according to state police.

Illinois’ Firearms Restraining Order law allows some individuals to request law enforcement to temporarily remove a person’s firearms if they are a danger to themself or others. It’s limited to those with specific relationships to the person named in the order.

The family never requested this order, nor did they press charges, so the incidents didn’t impact his gun purchases, according to law enforcement.

Spritzer added there is no universal rule dictating whether police can make the decision to remove guns on their own.

“If the police had a legal basis to conduct a more formal investigation, for example, that could have made a very big difference,” Spitzer said. “But police representatives have said that based on the information they had, at the time, when these events occurred, they didn’t have any basis for acting further.”

Lake County Illinois State’s Attorney Eric Rinehart reiterated at a news conference Wednesday that each situation is different.

“It is on a case-by-case basis and it would depend on the information they had at that time,” Rinehart said.

Generally speaking, some common threads tend to run through mass shooters, Spitzer said. That includes indicating in advance what their plans are, prior acts of domestic abuse and violence.

“It’s a tough call for authorities, there’s no doubt,” Spitzer said. “But there are times when action can be taken. And indeed, mass shootings have been prevented in the hundreds in recent years. And we know that from studies.”

The parents of the suspect dispute claims that their son was suicidal and threatened to kill them, according to the couple’s attorney Steve Greenberg. The suspect’s uncle said he lived with Crimo for several years and saw “no signs of trouble.”

After the shooting, authorities said he drove more than two hours toward Madison, Wisconsin, where he considered another attack. Ultimately, he didn’t carry out the plan because he wasn’t prepared, police said, and he returned to Illinois, where he was arrested hours after the Highland Park shooting.

Law enforcement found additional guns in his car when he was arrested.

Crimo now faces seven murder counts for each victim killed in the shooting at the time of the charges. He’s currently being held without bond.