The latest cash-bail reform plan: Give everyone a lawyer

- A Pittsburgh plan tries to tackle some of the biggest problems with cash bail

- With a lawyer, bails decline, nonviolent offenders get out but still appear at trial

- But it’s unclear whether it will save money and crime still increases

The Pittsburgh Municipal Courthouse. Photo credit: Allegheny County Photography

(NewsNation) — A Pennsylvania court system has launched a new kind of cash-bail reform.

Despite what could be considered common knowledge, there is no Constitutional right to a public defender assigned to you at your bail hearing. About half of U.S. counties don’t provide defense counsels at that stage.

But as of this month, most defendants at the Pittsburgh Municipal Court in Allegheny County will have access to public defenders at that initial hearing. It’s another attempt to get people out of jail who don’t need to be there and cut the costs, while avoiding the big problem that’s jeopardized other bail-reform efforts: too many people let out commit serious crimes.

“These were low-level, nonviolent offenders who were sitting in jail,” said Matt Dugan, the court’s chief public defender since 2020 who helped oversee the launch of the plan. “We knew that if we could just provide some information, some perspective to these [judges] setting the bond that we could probably get these folks out immediately.”

Cash bail on trial

Dugan leaves his job this month to run as the Democratic nominee for Allegheny County district attorney. He defeated the current district attorney, fellow Democrat Stephen Zappala, in the primary in part because Zappala was seen as not progressive enough on issues like bail reform.

Dugan said he would go further if he takes office.

“We’re never going to request cash bail,” he said.

Allegheny County’s experiment is happening amidst a larger debate about cash bail reform that’s taking place from coast-to-coast. States are moving to limit the use of cash bail, making certain crimes ineligible for it.

Reformers argue cash bail unfairly punishes people in poverty who haven’t even been convicted of a crime yet, and say these reforms make the system more fair. But opponents argue the reforms are leading to an increase in crime because they’re letting potentially dangerous people walk free before their trials.

In one high-profile example, the state of New York implemented reforms in 2019 that eliminated cash bail for a series of nonviolent offenses. After outcry over some individuals going on to commit crimes, New York changed its law to give judges more discretion to set bail.

In Illinois, a judge ruled in favor of 60 state prosecutors and called a recent cash-bail reform unconstitutional.

The Pittsburgh plan

In the case of Pittsburgh, new research suggests that providing public defenders at bail hearings has reduced the use of cash bail and pre-trial detention. But it may actually increase costs and at least one kind of crime, presenting county officials with a tradeoff and testing their commitment to reform.

Bail hearings at Pittsburgh Municipal Court are typically short. They usually last just four or five minutes, long enough for the judge to read charges, inform defendants of their rights and their court date, and set their bail.

These hearings cover every offense ranging from DUIs to homicides. In 2022, there were almost 14,000 arraignments in court.

The idea is to eventually have every arraignment feature a public defender. In 2017, the county offered public defenders to defendants at bail hearings during weekday business hours. In 2019, they expanded to include evenings, weekends and overnights.

This month, they plan to have public defenders at all arraignments from 9 a.m. through midnight during the week, with some gaps still present overnight, during the weekends and at the outlying district court locations.

The RAND Corporation studied Pittsburgh’s reform in 2019 and 2020. Because the city didn’t have enough public defenders to cover all defendants during those years, RAND was able to look at the difference between defendants with lawyers and those without.

Defendants with lawyers were 20% more likely to be released without cash bail than those who didn’t have a lawyer.

Also, the chances that a defendant would be in jail three days after their hearing also dropped by 10%.

There was no impact on whether defendants appeared at their next hearing, according to the RAND study.

But there is a potential downside in cost and crime.

According to a report the county commissioned, after the first year, 2017, of introducing public defenders at bail hearings, the court saw 111 fewer bookings and estimated a savings of nearly $150,000 in jail costs.

However, the court eventually expects to spend $500,000 to $600,000 a year to provide public defenders to all defendants at the bail hearings, according to the county. While the cost savings could also be higher than they were in 2017, there has not been another study by the county on cost savings since the program was expanded.

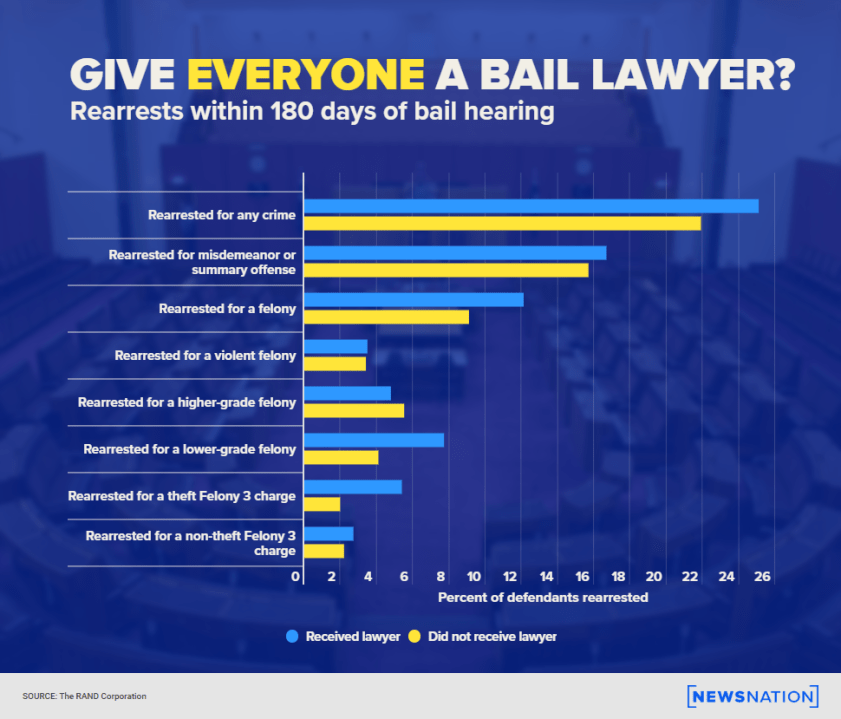

Also, a little more than 5% of the people who had public defenders were arrested within 180 days of the bail hearing for third-degree felony thefts, according to the RAND study. About 2% of the people without lawyers were arrested again.

There was no increase in violent crimes, and the spike in crime was largely driven by rearrests for those third-degree felony thefts, according to the report.

However, that increase in re-arrests could lead to additional costs, such as when police have to make additional arrests.

Dugan acknowledged “there’s going to be some tradeoff.”

“What I like is, we didn’t see an increase in violent crime… so I look at it relatively low-risk for the cost to incarcerate someone per day in the Allegheny County Jail but also the cost to society and that individual and collateral folks, family members, kids, that kind of stuff, to risk a potential small dollar amount theft down the line,” he said.

Andrew Capone, who is in charge of recruiting and retention at the public defender’s office, said the public defender’s office also connects defendants to drug, alcohol and mental health services to try to keep them from committing more crimes while they are out.

Progressives target Pittsburgh

Law enforcement has been among the most vocal critics of bail reform efforts nationwide, stating that poorly drafted and over-the-top reforms lead to an increase in crime.

The Pittsburgh Fraternal Order of Police did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Several magisterial judges who oversee the bail hearings also did not respond.

Neither did Zappala, the current district attorney who was beaten in the primary by Dugan, the chief public defender who supports the new plan. The two will face off again in the general election in November because Zappala accepted the Republican Party’s write-in nomination.

Dugan’s victory would be a win for progressives, who have been using district attorney races across America as a vehicle to reshape the criminal justice system.

Dugan’s campaign received more than $700,000 in advertising paid for by the Pennsylvania Justice and Public Safety PAC, which is funded by Demoratic megadonor George Soros. Also, the national PAC Color of Change used text messages and mailings to support Dugan, according to Pittsburgh’s public radio station.

One of the complaints against Zappala was that he specifically didn’t do enough to rein in cash bail.

“DAs have a whole lot of power when it comes to sentencing, pretrial detention, bail,” Danitra Sherman, the Pennsylvania ACLU’s deputy advocacy and policy director, told WESA radio. “A lot of people aren’t even aware of all the power the DAs hold,”

The race between Dugan and Zappala, Sherman told WESU, “was a great opportunity for us to raise awareness.”