(NewsNation) — Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have demonstrated a new technique for treating depression by stimulating deep brain areas noninvasively.

The study, published in Nature Mental Health, offers hope for more effective depression treatments without a need for drilling, using a combination of brain imaging and stimulation techniques.

Dr. Desmond Oathes, director of the Center for Brain Imaging and Stimulation at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, led a team that found depression and anxiety symptoms decreased by about a third, paving a new way for patients who don’t respond to medication or psychotherapy.

“It’s a noninvasive stimulation. So there are no surgeries or anesthesia, or anything like that,” Oathes told NewsNation.

How does it work?

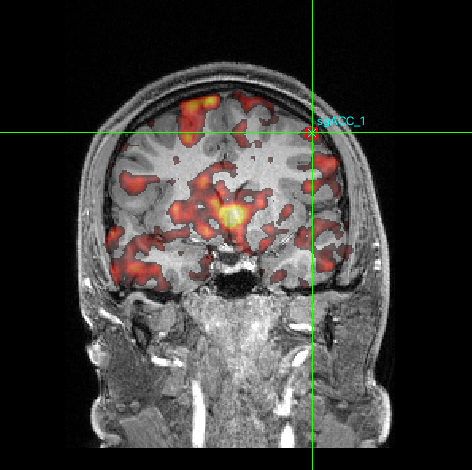

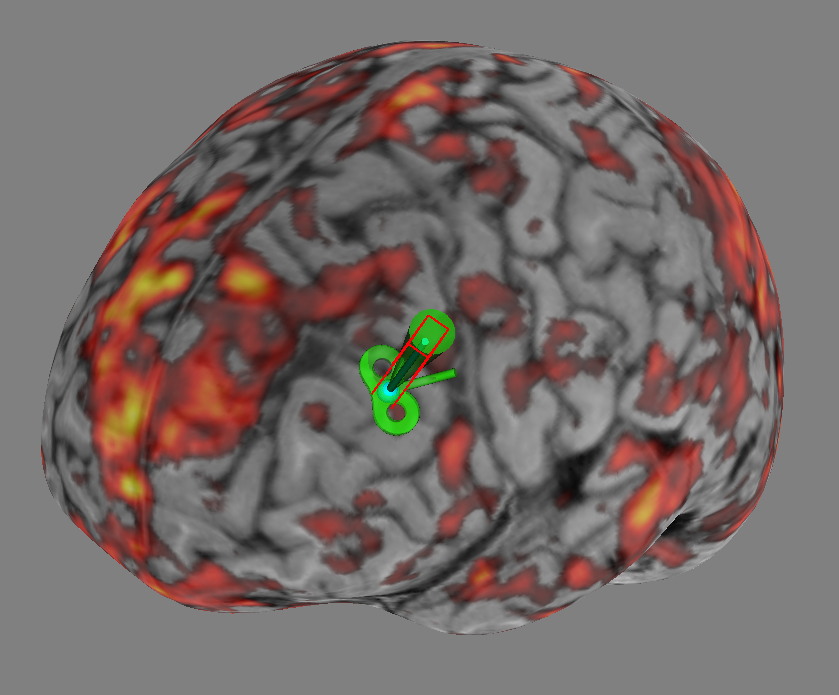

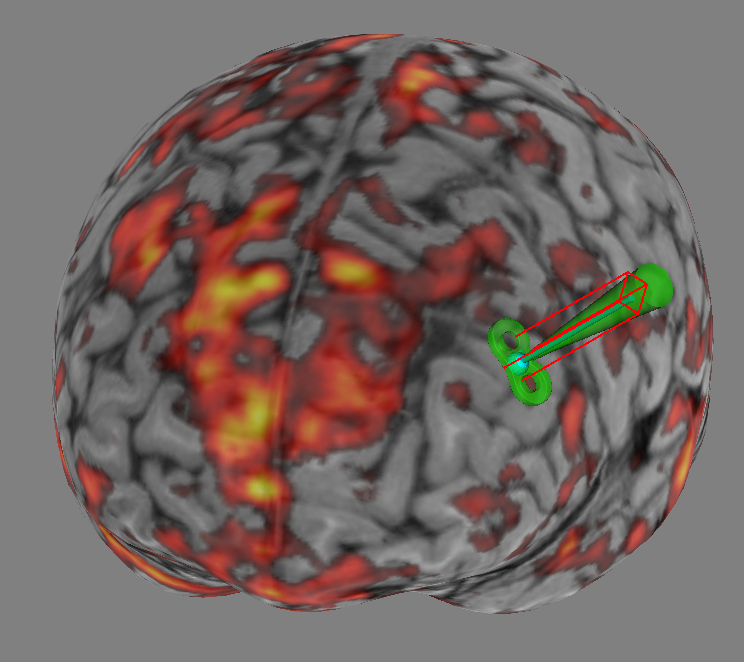

Researchers noninvasively stimulated a deep brain region linked to depression called the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC) using functional MRI (fMRI) with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

fMRI is a brain imaging technique that shows which parts of the brain are active when a person is thinking or performing tasks. It’s like taking a video of the brain at work, showing which areas “light up” during different activities.

Whereas rTMS is a treatment that uses magnetic pulses to stimulate specific areas of the brain. It’s akin to gently tapping on certain parts of the brain from the outside to change how they work.

“We can interrogate this black box of how the brain stimulation therapies are working,” Oathes explained. “We can also chase after some of these deep brain regions and show evidence that we can reach them non-invasively.”

The researchers use fMRI to create a detailed map of each patient’s brain, identifying which areas are involved in depression. They then use this map to guide the rTMS treatment, ensuring they’re stimulating the exact right spot for each patient.

“We thought we’d put these things together in this new way, where we’re stimulating the brain while we do recordings and try to link that to the symptom improvements in depression that we see,” Oathes told NewsNation.

Symptoms and results

Patients received thousands of stimulations over multiple days. The team measured depression and anxiety symptoms before and after the intervention.

The study involved 36 adults diagnosed with depression. The patients in the study were not taking any psychiatric medications because they did not respond to them.

“The reason why we chose the unmedicated patients is that we wanted to get this really pure brain measurement of what happens in response to the brain stimulation that didn’t get contaminated by having the online medications,” Oathes told NewsNation.

After just three days of sessions, participants showed a 34% improvement in depression symptoms and a 32% reduction in anxiety.

Potential as an alternative to medication

While already used as an alternative to medication in some cases, Oathes believes this personalized approach could offer more options for patients.

“Ultimately, what’s going to happen is that patients as individuals can kind of show their preference,” he said, noting that some may prefer brain stimulation to medication.

The treatment has fewer side effects compared to other brain stimulation therapies but does require in-person clinic visits and may not be covered by all insurance providers.

The study was a short intervention (3 days) rather than a full treatment, so it doesn’t provide information on long-term effects. Full treatments typically involve:

- 4 to 6 weeks of daily sessions over 5 consecutive days

- Or a newer form with 10 sessions per day over 5 consecutive days

Regarding long-term effects, Dr. Oathes said: “There’s some tendency that when you’re done with the stimulation for the symptoms, to start to slide back in general with this form of treatment.”

If symptoms return, patients can go back for more treatment.

Oathes said that a major upside is the absence of seizure risk, distinguishing it from electroconvulsive shock therapy (ECT).

The main side effects he said were minor: potential physical discomfort or tenderness at the stimulation site and possible headaches from the “thumping sensation.”

Future research

While the results are promising, the researchers emphasize the need for larger clinical trials with diverse participants.

Oathes and his team are now conducting a full clinical trial for depression and exploring the technique’s potential for treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

How common is depression?

The World Health Organization estimates 5% of the world’s population has depression, making it an incredibly common mental disorder.

Both the disease and treatment by antidepressants are on the up in the United States, with the CDC reporting a notable spike in prescriptions in adults from 2015-2018.

Since then, the COVID-19 pandemic has raised mental health concerns across the board. People aged 12-25 reported a 64% increase in antidepressant prescriptions in December 2022, a mighty leap felt after the onset of the pandemic.

NewsNation’s Anna Kutz contributed to this report.