NEW HAVEN, Conn. (News Nation) — Screening college students with just symptoms is not enough to contain a potential COVID-19 outbreak on college campuses for a fall in-person return, according to a new study published Friday in JAMA Network Open. Instead, universities may need to test students every two days, make some changes to space people out on campus and setup an isolation dorm.

The research laid out a possible solution for college campuses to consider in-person classes in the fall 2020 semester. The authors of the study are from Yale’s School of Public Health, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital’s division of infectious diseases

“The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic poses an existential threat to

many US residential colleges; either they open their doors to students in September or they risk

serious financial consequences,” the study’s authors wrote.

The analysis found several components to a safe reopening.

First, there would need to be a fast turnaround for test results. The researchers recommended eight hours.

The researchers said the most cost-effective and manageable way for colleges to implement testing would be to use one with modest sensitivity.

“Across all scenarios, test frequency was more strongly associated with cumulative infection than test sensitivity,” they wrote in the report.

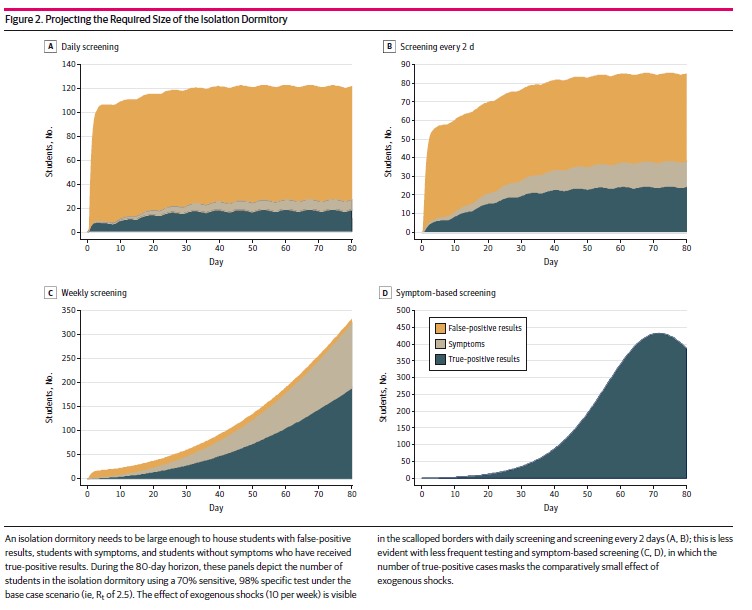

Using a computer model, they looked at what would happen if you had 5,000 students during an 80-day semester, and tested every day, every 2 or 3 days, or weekly. The model also looked at just screening of people with symptoms.

The model assumed 10 students had the SARS-CoV-2 infection when the semester began.

“Varying the initial number of asymptomatic infections between 0 and 100 did not materially change our findings,” the report said.

By the semester’s end, 162 students were infected if testing was done daily. 1,840 students were infected if the testing was done weekly.

Part of the scenario required an isolation dorm, with individual rooms and bathrooms. In the sample of 5,000 students, the dorm would need to be able to hold not just those with actual cases, but also students with false-positive results.

The scenarios look specifically at the student populations and require several factors only in the hands of students and administrators, and not something a computer can predict.

“Strict adherence to hand-washing, mandated indoor masking, elimination of buffet dining, limited bathroom sharing with frequent cleaning, dedensifying campuses and classrooms, and other best practices,” the report said could help reduce to a best-case scenario on campus.

The final factor is cost.

“Obtaining an adequate supply of testing equipment will be a challenge. On a college campus

with 5,000 enrollees, screening students alone every 2 days will require more than 195,000 test kits

during the abbreviated semester,” the report said.

They estimate in the computer simulations presented that testing every 2 days with 70% sensitivity, would likely cost $470 per student for the semester, depending on how well people adhere to hand-washing and other guidelines.

Being a simple model, the researchers said there are several limitations. They also didn’t include contact tracing into the research “due to its implementation challenges.”

“However, our results suggest that with frequent enough screening, contact tracing would not be necessary for epidemic control,” the researchers wrote.

For transparency, the research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of

the National Institutes of Health and the Steve and Deborah Gorlin Research Scholars Award from the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research.

“We believe that there is a safe way for students to return to college in fall 2020. In this study,

screening every 2 days using a rapid, inexpensive, and even poorly sensitive (>70%) test, coupled with strict interventions … was estimated to yield a modest number of containable infections and to be cost-effective,” the researchers wrote. “This sets a very high bar—logistically, financially, and behaviorally—that may be beyond the reach of many university administrators and the students in their care.”