(NewsNation) — From coast to coast, local government leaders and schools are debating what to teach in America’s public schools, and topics like critical race theory make headlines.

These debates are often so contentious it can appear that we can’t possibly agree on what we should be teaching to America’s children.

But what if we actually agree more than we think we do?

A new report by the group More In Common found what researchers called a “perception gap” on either side of the political spectrum, in that both sides agree on how to teach history more than is often assumed, but they also tend to think the other side is more extreme than they actually are.

The group’s director, Stephen Hawkins, listed a few items Republicans and Democrats agreed on.

“They agree that there needs to be a factual history that teaches both the parts of American history that are exceptional or distinctive about the story and the parts that are really ugly — and that might cause us to feel shame,” Hawkins said. “Both sides want those in the picture.”

As an example, clear majorities of Democrats, Republicans, independents and people across racial lines believe that it’s important to teach every American about slavery, segregation and Jim Crow laws. Additionally, they believe that American figures such as George Washington and Abraham Lincoln should be admired.

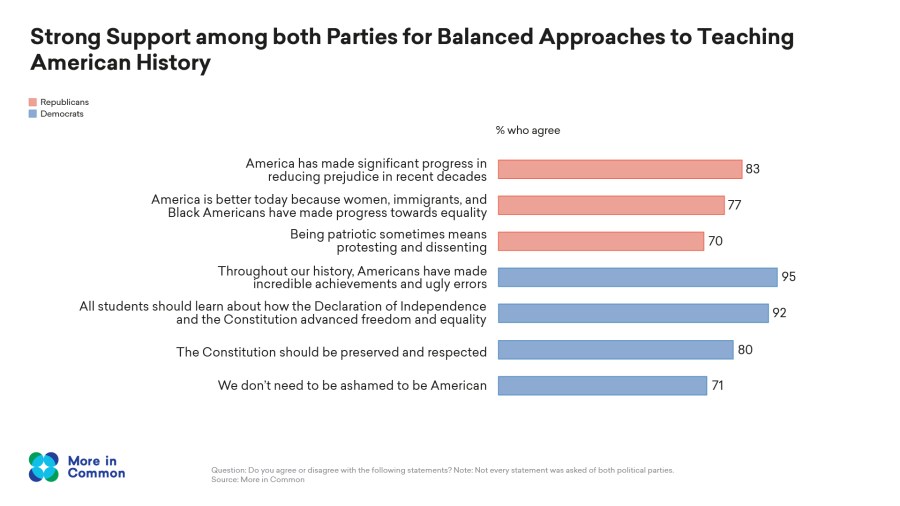

The majority of Republicans surveyed favored emphasizing the importance of protest and the progress America has made in reducing prejudice. Most Democrats agree that Americans don’t need to be ashamed of being American and that the Constitution should be respected.

“There’s broad support for teaching our shared American history, which would be the big national wars, big economic episodes, climate events, and also for teaching minority history… Republicans three out of four say we should be teaching minority history as well,” Hawkins said.

Hawkins believes the disconnect comes when both sides misunderstand the other side’s view and exaggerate their differences.

“Republicans think Democrats don’t want to talk about America’s exceptional founding, for instance, with the Founding Fathers, and Democrats think Republicans don’t want to talk about slavery and Jim Crow,” he said. “Both sides are wrong on that account.”

For instance, surveyed Democrats expected only a third of their Republican counterparts would accept the notion that “Americans have a responsibility to learn from our past and fix our mistakes.”

Republicans told researchers less than half of Democrats would agree that “all students should learn about how the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution advanced freedom and equality.”

In both cases, more than 90% agreed with those statements.

There are, however, areas of substantial difference between Americans. When the survey asked whether “America needs to do more to acknowledge past wrongs,” half of white Americans agreed, compared to more than three-quarters of African Americans, Hispanics and Asian Americans.

And it’s not clear whether agreements on questions in the survey mean that Americans can reach a consensus in actual debates at school boards or state legislatures, where the questions over curriculum may be over more niche issues than broad principles.

Still, the survey’s findings show that there is at least some consensus on the way we should be teaching American history.

Hawkins noted that while many people want to emphasize past wrongs and many people believe that lingering on past wrongs can prevent us from moving forward, there’s not necessarily a contradiction between these two beliefs.

“You can both resolve the past and not be obsessed with it, not fixated on it,” he said. “I think so much of our national dialogue on these sorts of issues can fall into these binaries, when (in) reality most Americans just seem to have more of a capacity for holding that tension and believing in a kind of moderation between two values or between two goals.”