Book bans in the US: Challenges to remove books up in 2021

Preschool Girl picks a book at the library.

(NewsNation) — Efforts to ban or remove books from school libraries skyrocketed last year, catapulted by prominent political figures advocating for parental choice in education.

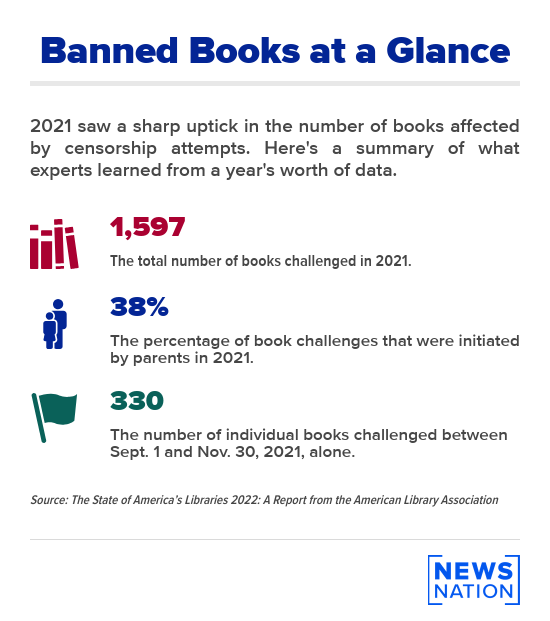

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom tracks challenges issued to remove books. It found that in the first three months of the 2021 school year alone, more than 330 unique cases of challenges were reported. That’s twice the number of challenges filed in all of 2020. By the year’s end, the association tracked 1,597 total challenges, more than half of which were reported at schools and school libraries.

“I would say in most of the past few years, until about the middle of 2021, the most common report is to have one or two books being challenged at the same time,” said Jonathan Friedman, director of free expression and education at the non-profit PEN America. “Fast forward to today — now the reports most often have, I would say, at least five books being challenged at once, if not 24 or 100, or 282 in one district.”

Challenging books — that is, filing a complaint to have the book removed or banned — isn’t a new concept. But increasingly, challenges aren’t following traditional protocol, according to research from PEN America. Challenges overall are happening more frequently, too, often against books with LGBTQ, racial or sexual content.

Those opposed to removing books from the classroom cite First-Amendments protections, diverse perspectives and representation as reasons to allow children what some activists have called “freadom.”

On the other hand, advocates fighting to pull certain books from the shelves say their children have access through their schools to books with descriptions of sexual acts, violence and abuse that is too graphic for young minds.

A recent NewsNation/Decision Desk HQ poll found that about 63% of voters believe parents should have moderate or a lot of control over public school curriculum.

Hernando County, Florida, father Monty Floyd is among the parents calling for certain books to be removed from school shelves.

“Basically, they’re pushing sexualized topics or stuff that’s way too mature or graphic for underage minors to be exposed to,” Floyd said. “Those decisions are more suited for parents.”

Although he’s chosen to homeschool his own children, Floyd now is running for a local school board position. He connects with voters through a series of YouTube videos dubbed “Inappropriate Storytime” showcasing books that are available to children in the local school district.

“Even if I wasn’t running, I would still be down there as a homeschool parent at the school board meetings, just raising H-E-double hockey sticks and I would be fighting just as hard,” Floyd said.

Several of the books Floyd and his supporters have taken issue with are among some of the most frequently challenged books of 2021.

Some of last year’s most challenged books included “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe, “Lawn Boy” by Jonathan Evison, “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson, and “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas.

Many of last year’s top banned books were challenged for LGBTQ content or were argued to be sexually explicit.

“If you combine those issues, sex education, or sex, LGBTQ characters, and books about race and racism, you capture easily 75% of all the books that have been challenged,” Friedman said.

School districts aren’t bound to a universal process that must be followed when a book is challenged, but they often rely on standards set out by groups such as the American Library Association.

“The way that policy works in most places is that it begins at the school level,” Friedman said. “And then there’s a kind of school-level policy process and review challenge, which then can be appealed to the district level. This way, the initial decisions are highly local rather than being made at the district level.”

Recently, however, that process has fallen to the wayside, Friedman said.

The ALA report states 20% of bans were initiated by lawmakers or school boards.

PEN America tracked challenges from July 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022 to ban books, authors and illustrators from specifically school libraries and classrooms.

It found 41% of those challenges were tied to directives from state officials or elected lawmakers to investigate or remove books in schools.

Additionally, 33 districts where library books were been banned had either no public or transparent policies accessible online, or the policies fell short of certain First-Amendment safeguards, PEN America found.

“I think part of it is very much driven by fear,” Friedman said. “We’ve seen politicians get very involved in this and legislators suggest new bills in the state legislature to deal with books in schools…I think a lot of people are feeling the heat of that moment.”

Floyd said having certain books readily accessible to children in a classroom setting without asking for a guardian’s permission might infringe on a parent’s wishes.

“If a parent is really like ‘I want my kid exposed to that stuff,’ then they can go to the public library and check a copy out and make sure their child reads it,” Floyd said.

The debate is playing out on a much larger stage, too.

In Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott directed school boards throughout the state to remove books that he deemed “pornography.”

A group of residents in Wyoming filed criminal complaints against public library officials who shelved books some said were obscene in the children and young adults sections. Ultimately, no charges were filed.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Utah launched an investigation in November after nine titles were removed from the shelves pending an investigation into complaints from parents. The district later restocked the books and changed their book review and selection policies.