Can taking a trade-school approach solve our teacher shortage?

Clarksville, Tenn. (NewsNation) — Rose Guerrero Ofarril thought she would make a good teacher. But a few months shy of high school graduation, fate and finances intervened.

She found out she was pregnant. Despite working three minimum-wage jobs, she knew she couldn’t afford her own apartment, car and tuition. Her family didn’t have financial means to help her.

“At the time, I had no clue what I was going to do,” said Guerrero Ofarril, now 21 and three years removed from that crisis. “College is expensive. I wouldn’t, I don’t know how I would afford it.”

Then she heard of a teacher residency program at the local Clarksville-Montgomery County School System. She could learn on the job while getting an education degree from a local university. There would be no cost for tuition, books and testing, and she’d receive a salary of $30,000 and health care benefits for her on the-job training.

The first-of-its-kind apprenticeship program began in 2018 with the goal to increase teacher diversity within the district. But now schools across the country are taking notice as staffing shortages due to burnout, COVID-19 concerns and fewer graduating teachers have created a crisis.

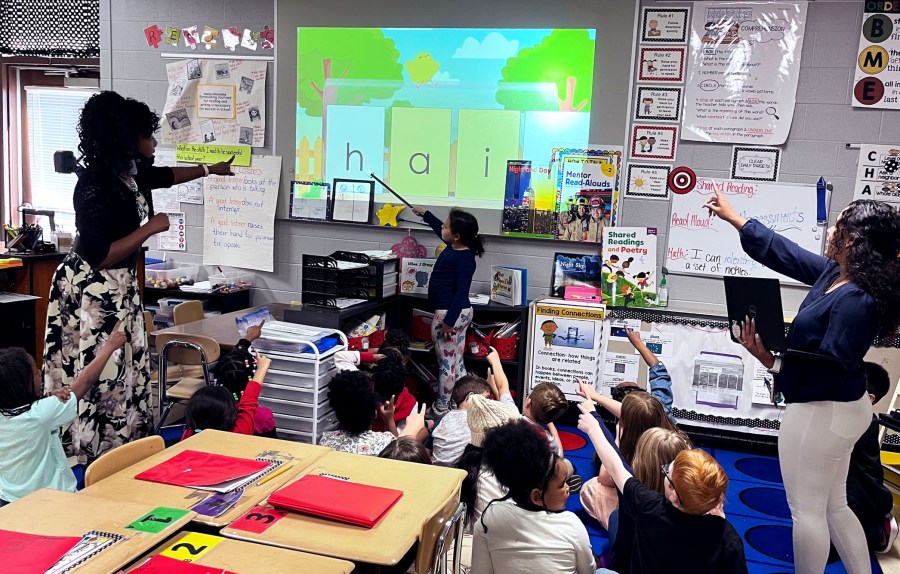

The method combines in-the-classroom training under a “master teacher,” with twice-weekly college classes in the evening. Residents gradually get more control of the classroom. A teaching certification takes three years to earn, or one year for those with a bachelor’s degree.

“If you were going to be a plumber, you’d work with a master plumber at the same time you’re getting your certification,” said Dr. Sean Impeartrice, chief academic officer in Clarksville-Montgomery. “This is the same model: They’re learning on-the-job competencies it takes to be a teacher.

Proponents say the residency gets participants working in the classroom immediately, leading to teachers who are more prepared and less likely to quit long-term. Clarksville-Montgomery has about 80 residents slots each year, with graduates going on to be placed in the average 400 openings the district has each year.

A growing solution

A nationwide teacher shortage has built for years as teachers burn out under the stress of three school years impacted by COVID-19. More than half of educators say they are ready to leave teaching, and 61% of school vacancies are due to the pandemic, according to a recent report by the National Council of Education Statistics.

Colleges churning out teachers can’t keep up. Tennessee, for example, graduates 700 fewer would-be teachers than it did in 2015. Currently there are 2,200 vacant teaching jobs across the state.

That’s compounded by the high cost of a bachelor’s degree, which all 50 states require for a teacher to get certified. The average college student has a $400 monthly payment upon graduating, according to Lending Tree, an online loan marketplace.

At least 12 states have a similar residencies. But most only work with high schoolers, or only work with those who have degrees from other fields.

Clarksville-Montgomery’s tactics are unique in that it reaches both untapped pipelines while increasing retention rates. Early data shows teacher residents may be more likely to stay in the district. In the past three years, 87 percent of graduating teachers are still working in the district.

While it’s still too early to call that data conclusive, consider that nearly 50 percent of teachers quit the profession within their first five years, according to the National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future.

Sixty-four school districts in Tennessee have begun their own programs, according to the district.

Stability while learning

In November 2021, Clarksville-Montgomery’s program was the first in the U.S. to be recognized by the Department of Labor, which means students will have more access to funding for things like transportation, food and child care.

About one-third of the participants come from diverse backgrounds, district officials say. Plus, lowering the financial bar increases the chances low-income students, first-generation college graduates and parents can finish the program.

It’s also creating better classrooms for poorer elementary and high school students, as experienced teachers switch schools to be master teachers. And the extra resident teacher in the classroom helps support kids with behavior or learning difficulties, which are more common in poorer schools.

“The general trend is that lower economic schools have trouble hiring good quality teachers,” Impeartrice said. “This reverses that.”

Still, the cost of the program often rests on individual schools or districts to find. Clarksville-Montgomery’s 3-year residency costs about $9,500 total per student, plus an annual salary. The district pays for it through an ever-changing mix of local, state and federal grants, its education budget and federal student loans funding.

Plus, starting a program like this is complicated. Without a lot of research and strong partnerships between local colleges and workplace service organizations, new programs “will have the attrition — because they don’t provide the wraparound services these students need,” Impeartrice said.

Now in her final year of training, Guerrero Ofarril says the program offered stability she needed as a new parent — a consistent paycheck during school and child care so she could attend classes.

“If our grades were going down, (other students in my cohort) were like, ‘Hey, are you good? What do you need from me? How do you need my help?’” she said, adding her mentors supported her through challenges that could have set her back academically and financially.

While in the residency, she had complications with her second pregnancy. “I got put on bed rest for five months,” she said. “But it wasn’t like … ‘What am I going to do now? They’re going to fire me. How am I going to support these kids? How am I going to pay the bills?’ No, I had that job right there the whole time waiting.”

Instead of worrying about student loan repayments, Guerrero Ofarril is planning to buy a house this fall. She’ll start as a first-grade teacher at Minglewood Elementary School.

“Being at the end, it gets more exciting because you’re like, ‘Wow, I really made it this far. I’m really about to graduate college in August. Like is that real? Is that really happening?’ Yes, it is.”