Mississippi city honors Freedom Rider legacy 60 years later

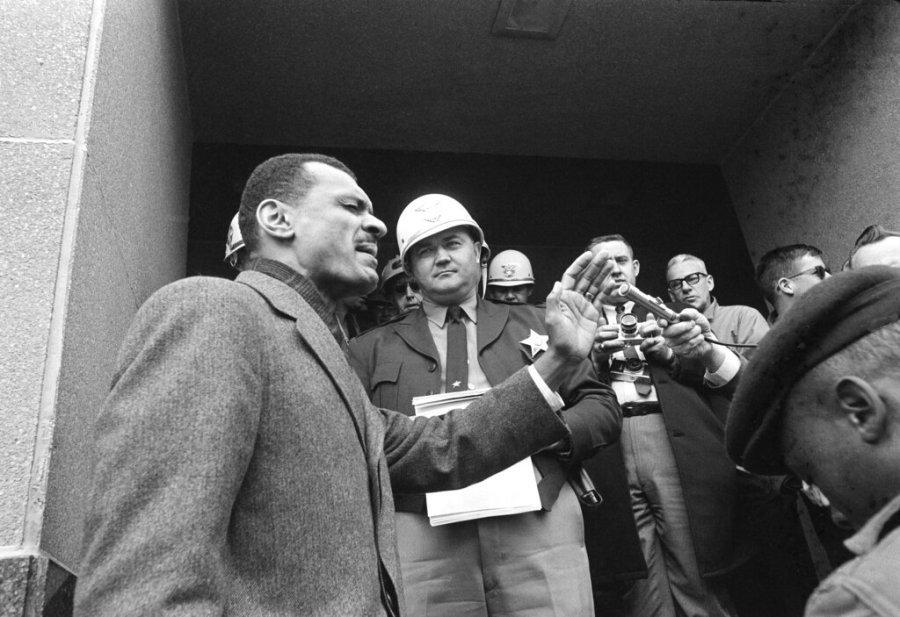

FILE – In this Jan. 4, 2012, file photo, civil rights activist C.T. Vivian poses in his home in Atlanta. Vivian, who worked alongside the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., and served as head of the organization co-founded by the civil rights icon, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and died in July 2020 in Atlanta. The mayor of Jackson, Miss., has declared Wednesday, May 26, 2021, as C.T. Vivian Day in Mississippi’s capital city. (AP Photo/David Goldman, File)

JACKSON, Miss. (AP) — Mississippi’s capital city is honoring the civil rights activism of the late Rev. C.T. Vivian 60 years after he and other Freedom Riders were arrested upon arrival in Jackson as they challenged segregation in interstate buses and bus terminals across the American South.

After several days in a local jail, the young activists were transferred to Mississippi’s notorious Parchman prison, where guards beat Vivian and others — one of many times that Vivian faced violence as he worked to dismantle systemic racism and injustice.

Jackson Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba proclaimed Wednesday as C.T. Vivian Day. The mayor’s wife, Ebony Lumumba, presented the proclamation to one of Vivian’s daughters, Denise Morse, at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum.

“Rev. Vivian remains a source of inspiration for leaders and advocates for justice at every age, because life teaches us that, among other things, we are never too young, never too old, never inexperienced to be on the front lines of this battle for justice,” said Ebony Lumumba, a professor of literature.

Cordy Tindell Vivian began challenging segregation in Illinois in the 1940s, became more involved with civil rights activism when he attended seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, in the 1950s and later became an adviser to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Vivian was 95 when he died July 17 in Atlanta — the same day that his friend and fellow civil rights activist U.S. Rep. John Lewis died of cancer at age 80.

In May 1961, Vivian was 37 and almost a generation older than Lewis, Diane Nash and other college-age Freedom Riders who set out from Nashville on buses into the Deep South. A violent white mob attacked Lewis and others in Montgomery, Alabama.

Vivian joined the other Freedom Riders days later in boarding another bus from Montgomery to Jackson. Mississippi’s segregationist governor, Ross Barnett, had cut a secret deal with U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy: Buses carrying Freedom Riders would be guaranteed safe passage once they crossed into the state, but the activists would be arrested in Jackson.

Black-and-white jail mugshots of Vivian and other Freedom Riders fill a gallery in the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum that opened in late 2017.

Morse lives in Fayetteville, Georgia, and visited Jackson for the first time this week. In the civil rights museum Wednesday, she looked proudly at her father’s mugshot and another photo that showed him, Nash, Bernard Lafayette and other activists in Nashville.

Morse said her father never bragged about his activism.

“He talked about concepts and values,” Morse said. “But he rarely talked about who he knew or where he’d been. He was more concerned about nonviolence and justice. That’s what he talked about.”

During his final years, Vivian worked on a book about his life with author Steve Fiffer. “It’s in the Action: Memories of a Nonviolent Warrior” was published in March.

Dozens of people gathered at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum on Wednesday to hear about Vivian from Morse and Fiffer, with the author appearing by webcast from his home in Evanston, Illinois.

The presentation started with February 1965 TV news footage that grabbed international attention. It showed Vivian trying to help Black residents register to vote in Selma, Alabama. Face-to-face with a recalcitrant white official, Vivian said: “You can’t keep anyone in the United States from voting.” The sheriff soon punched Vivian in the face, knocking him to the ground.

Three weeks later, thousands of people later marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. Months after that, Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Vivian received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013 from then-President Barack Obama, a man who was born months after Vivian and other Freedom Riders were arrested in Mississippi.