Solving decades-old missing person cases with DNA data

393282 04: A digital representation of the human genome August 15, 2001 at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Each color represents one the four chemical compenents of DNA. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

(NewsNation) — In 2002, construction workers in Northeast Texas located the remains of a woman. Police were unable to identify who she was.

Authorities told local news media she had been there a while, but they didn’t have much more to go on.

The woman became known as Gregg County Jane Doe 2002. There are an estimated 40,000 unidentified remains in the United States. The inability to identify these remains denies closure to friends and family members who have lost their loved ones.

But in this case, officials were able to make a breakthrough this summer with the help of a nonprofit called the DNA Doe Project, which consists of a group of volunteers who work with police to use forensic genealogy to identify unidentified remains.

The DNA Doe Project was able to use samples of DNA to trace her maternal line. They eventually identified her as Pamela Darlene Young, using DNA from her daughter to confirm her identity. In this case, Young’s family had never reported her missing, believing she lived a transient life.

“She was nowhere in the system, she was literally left out in the fields, with no one to claim her. So it’s sad, and a lot of the stories of the Does that we work are very sad,” said Pam Lauritzen, the media director at the DNA Doe Project.

Since its founding in 2017, the DNA Doe Project has helped identify dozens of unnamed deceased persons.

“Our co-founders, Dr. Margaret Press and Dr. Colleen Fitzpatrick, got together, had the idea that, oh, genealogy and the whole burgeoning industry of consumer DNA testing could be combined to build family trees for unidentified people and figure out who their relatives are and then figure out who they are,” Lauritzen said.

Law enforcement and medical examiners turn to DNA Doe Project when they have remains they can’t identify. DNA Doe Project consults with them about the best lab to use in order to extract DNA.

The organization then uploads the person’s DNA profile to public databases. DNA Doe Project uses two in particular: GEDmatch.com and FamilyTreeDNA.com.

“At those sites, a lot of ordinary people have uploaded their DNA profiles,” Lauritzen said. “So when we’re able to upload the profile of an unidentified person, then we can see who else in the database matches as a biological relative to this unidentified person.”

They then use genealogy techniques to build family trees.

“(We) find that intersection, that exact right branch of the family tree that contains this person that we’re searching for and then that person becomes the candidate,” she said.

Out of the 177 cases it has taken on, DNA Doe Project — which is composed of around 100 volunteers and a small paid managerial staff — has solved around 80 of them. One of the challenges in solving these cases is that the organization relies on the two aforementioned DNA databases in order to match unidentified people with families.

“So most of the consumer sites like Ancestry.com, 23andme, they don’t allow law enforcement cases in their system. So a law enforcement agency can’t have a DNA profile for an unidentified person and upload it to Ancestry and work on matches (in) Ancestry,” Lauritzen said.

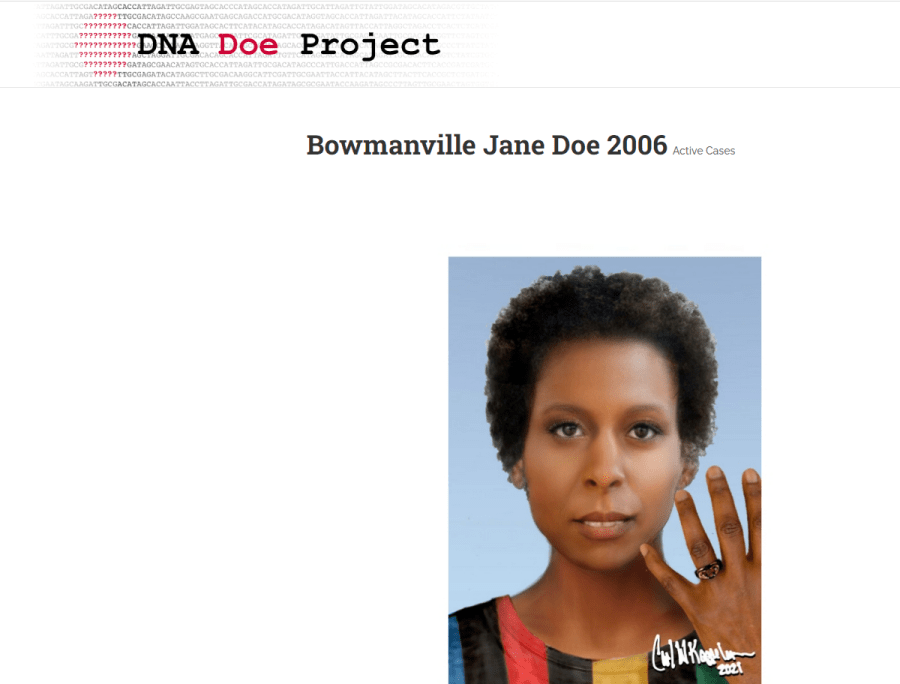

While many unidentified deceased belong to minority communities, these same groups tend to have a small presence in the public DNA databases because fewer members of these communities have uploaded their personal data to these websites.

“Racial minorities in the United States are hugely underrepresented in these public databases. … So when we work on cases of someone who’s African American, someone who’s a murdered indigenous woman for instance, you know, the matches are really few and far between in the system just because there isn’t a lot of data,” she said.

One of DNA Doe Project’s current collaborations involves working with Intermountain Forensics and the Utah Cold Case Coalition to help identify victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

They are looking for people who had family in Tulsa in 1921 to offer records or family trees that could help with the identification process; people can also volunteer their own DNA for comparison with unidentified remains.