ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (KRQE) — A team of researchers from several institutions dubbed a 6.7-foot-long shark that lived 300 million years ago “Godzilla Shark” after discovering a fossilized skeleton in the Manzano Mountains about 30 miles southwest of Albuquerque, New Mexico.

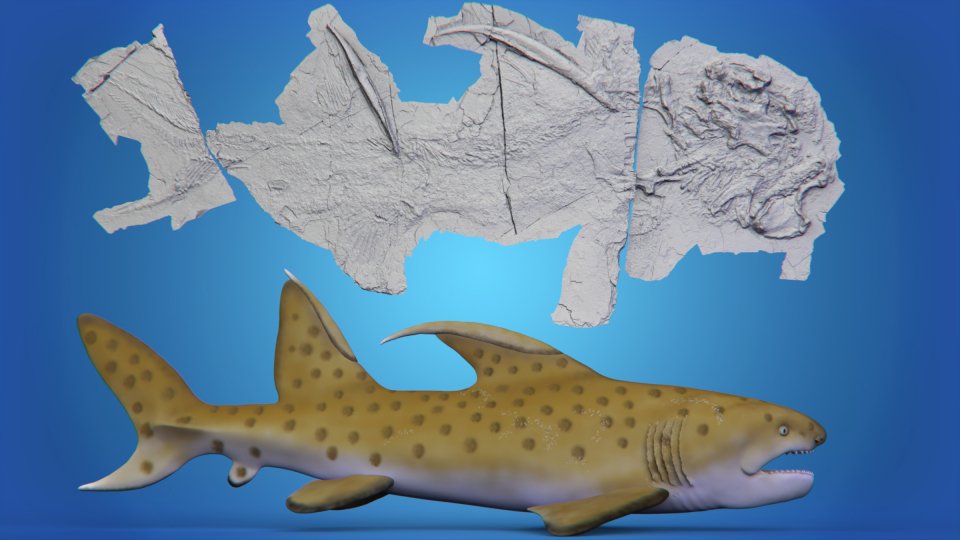

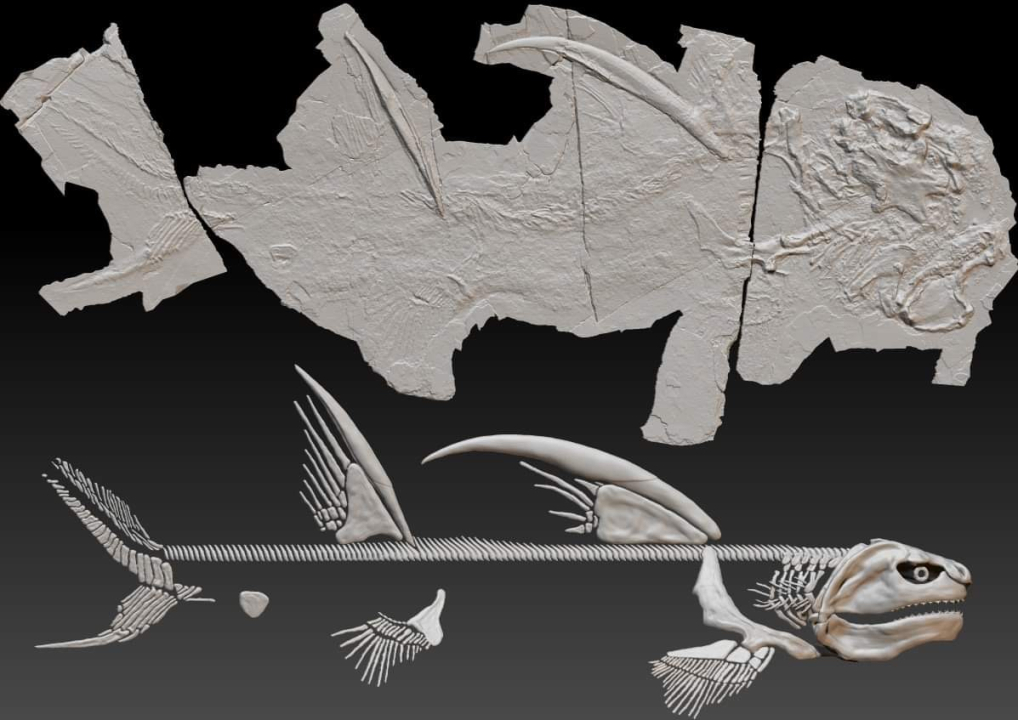

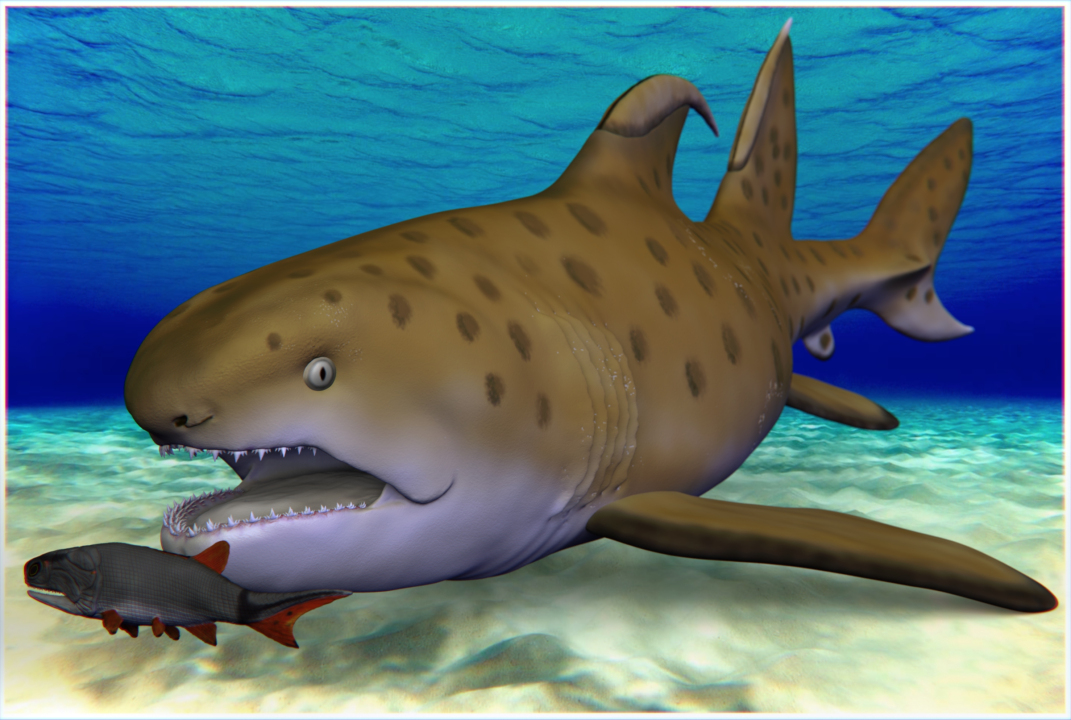

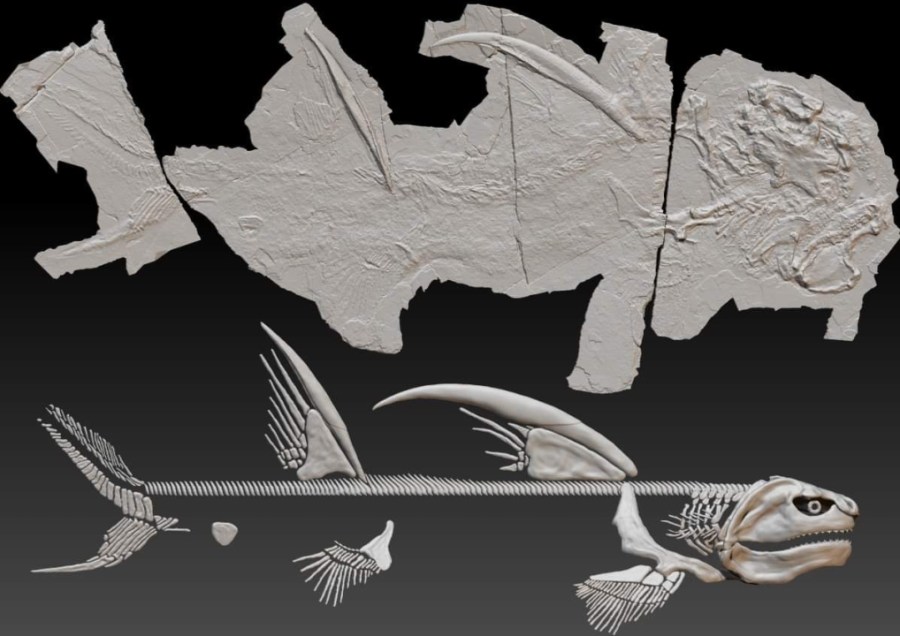

According to the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, the complete skeleton of the shark named Dracopristis hoffmanorum was discovered and identified to have 12 rows of teeth along with two, 2.5-foot-long fin spines on its back.

A press release from NMMNHS states that the features of the shark resulted in its popular nickname “Godzilla Shark” when it was initially discovered in the Manzano Mountains in May 2013. The museum said the name Dracopristis hoffmanorum, or Hoffman’s Dragon Shark, recognizes the creature’s Godzilla-like traits as it’s the largest fish found at the site so far and has large jaws and spines. The name also honors the Hoffman family who owns the land where the shark fossil was collected.

The Museum reported that a group of scientists who were participating in a scientific meeting at NMMNHS visited the mountains to learn about the rocks as well as fossils of the late Pennsylvanian Period plants and animals preserved there.

Paleontologist and program coordinator of the Maryland-National Capital Parks and Planning Commission’s Dinosaur Park, John-Paul Hodnett, who was a graduate student at the time, made the discovery.

“I was just sitting in a shady spot using a pocket knife to split and shift through the shaley limetones, not finding much except fragments of plants and a few fish scales, when suddenly I hit something that was a bit denser,” stated Hodnett in the press release. “At first, I thought what was flipped over was the cross section of a limb bone, which was exciting as no tetrapod had been found at that site before.”

A team from NMMNHS was able to expose more of the fossil while the rest of the meeting participants returned to the museum. According to the press release, the next day Hodnett was told by the museum fossil preparatory that the creature wasn’t a tetrapod but a large shark.

Curator of paleontology at NMMNHS Dr. Spencer Lucas urged Hodnett to research the fossil which was determined to be the most complete ctenacanth shark fossil to be discovered in North America. The museum reports that the following seven years were spent working in the preparation lab in order to clean and stabilize the fossil, research the discovery and compare it to other sharks. Hodnett’s team was able to identify it as a new kind of ctenacanth shark.

A CT scan of the fossil by Presbyterian Rust Medical Center in Rio Rancho aided research around the discovery.

According to the museum, the shark’s large dorsal fin spines were used as a deterrent against larger predators. “In the same rocks that yielded the fossil of Dracopristis, we have found teeth of a larger shark called Glikmanius, which is known almost worldwide at this time, and it would have been a large and dangerous predator,” said Hodnett in the press release.

The museum explained that the skeleton provides a new look at how ctenacanths fall in the family tree of sharks. Additionally, NMMNHS states that Dracopristis and other ctenacanth sharks display an individual evolutionary branch of sharks that split off from the modern sharks and rays about 390 million years ago but that went extinct by the end of the Paleozoic Era about 252 million years ago.

The research team was made up of Hodnett, Eileen D. Grogan and Richard Lund of St. Joseph’s University in Pennsylvania, Spencer G. Lucas, Curator of Paleontolgy at NMMNHS, Tom Suazo, former fossil preparator at NMMNHS, David K. Elliot of Northern Arizona University and Jesse Pruitt of Idaho State University and was assisted by NMMNHS.